History of the Spanish National Team: part 3: Olympic disappointments and the birth of the "narrative of failure"

The commonly heard complaints about Spain's bad luck at major tournaments, which were finally put to bed with victories at Euro 2008 and 2012 as well as the 2010 World Cup, are not an invention of journalists in the 80s and 90s, as one might think. The so-called "narrative of failure" began to take hold all too early in the national team’s history: back in the mid-1920s, disappointed voices emerged and then they got carried away with pessimism all too easily.

In the second half of the 1920s, the aura of optimism surrounding the national team had well and truly waned. Between 1924 and 1929, the national team lost its air of invincibility and failed to win a medal at the Olympic Games once again. In what was a particularly disappointing third decade of the 20th century Spain saw Olympic failure in 1924 in Paris and again in 1928 in Amsterdam.

Spain’s goal of maintaining its status as a world footballing power was fading and it paid the price for their failures in the long term by not being seeded for the 1934 and 1950 World Cups.

At the same time it was not all doom and gloom, there were some notable victories along the way that were considered "historic" at the time and even up to the present day, such as the 1929 victory over England.

In the 1930s, the team once again sparked great hopes with its performances at the 1934 World Cup in Italy and by achieving some resounding victories, such as against Germany in 1935.

The narrative of failure

If 1920 and the years that followed saw the birth and consolidation of the "narrative of Spanish fury" in terms of their playing style, the failures in 1924, 1928 and the way they were knocked out of the World Cup in 1934 gave way to a new "narrative", that of failure and negativity. The feeling of doom and gloom began to surround the national team’s performances. Some of which stemmed from bad luck, such as the own goal by Pedro Vallana that led to Spain's elimination from the 1924 Olympic Games, others from unfavourable refereeing decisions, as in the Italy-Spain World Cup match in 1934 or even adverse weather conditions conspired against the National Team in the 7-1 defeat by England in 1931, which was blamed on the bad state of the pitch following heavy rain.

The first disappointment, from which this "narrative of failure" stems, came with a name of its own,Italy, and it happened twice. The national team drew 0-0 with Italy in a friendly in March 1924 in what was already a warning of what was to come.

Spain arrived at these Olympic Games with high hopes of doing something special after their silver medal in 1920. The sports newspaper Madrid Sport, following the disappointing goalless draw with Italy in March, lead with the headline "We are confident in our future" and did not hesitate to exclaim that "we have improved in terms of technique, we are playing much more freely than at the last Olympics, our characteristic drive to win remains, the enthusiasm in the face of the enemy is as strong as ever".

Moreover, the Spanish team, led by coach Pedro Parages, not only had four Olympic runners-up still in the team (Zamora, Vallana, Belauste and Samitier) but also came surrounded by optimism, spurred on by the fans and the press at the time.

The draw brought about a one-off match against Italy. A week earlier, the euphoria was palpable when, in an Olympic warm-up match, the Spanish team beat Newcastle 1-0 in Bilbao. Spain and Italy played the first match of the Olympic football competition on 25 May at the Olympic Stadium in Colombes. It was a very intense, hard-fought match in which Spain were a man down from the 55th minute onwards after Larraza was sent off. Despite all this, until the 80th minute the national team imposed their rhythm and their playing style and even had the best chances to take the victory.

However, with a quarter of an hour to go, a counter-attack from winger Conti ended with a pass pulled back across the box and the ball ended up being put into his own net by Spanish defender Pedro Vallana. The team were out of the Olympic Games and could not go on to repeat the medal winning success they had achieved four years earlier.

This emotional blow was all the greater because the expectations for the national team had been so high. Such was the attention surrounding the match that the king himself followed every last detail of what was happening on the pitch.

Journalist Acisclo Karag told Marca many years later:

"King Alfonso XIII was a massive fan and at the Olympic Games in Paris, held in 1924, he asked me to send him an update by telegram every ten minutes during the Italy-Spain match".

And as football was already a national sport and followed by the masses in the 1920s, not just the elite, the Spain - Italy duel also struck a chord with people across all sections of society. The sports daily Marca’s great journalist of the day, Cronos, a child at the time, later recalled:

"In those days, the newspapers even made space in their column inches despite the famous robbery of the Andalusia Express train at the time to make way for articles on the unexpected defeat. People suddenly forgot the thieves Piqueras, Honorio Sánchez, Donday and Navarrete, and turned their attention towards that unfortunate own-goal by Vallana that knocked Spain out of the match".

Another Olympic disappointment

The disappointment was repeated four years later at another Olympic Games in 1928. In Amsterdam, Spain and the rest of the national teams took part with their senior teams, although some did so with non-professional players and others were more lax in complying with this rule of amateurism.

Six years later, José Ángel Berraondo, who had already coached the team in 1920 and 1921, was back in charge of the team.

The coach decided to go to the Olympic Games having put together a squad of players not considered to be professionals, which meant that the big names of the time (especially Zamora and Samitier) were left out of the squad. In the end, Berraondo could not count on Goiburu because of academic commitments or Errazquin, who was born in Argentina.

Berraondo's team should have started off by taking on Estonia but they withdrew from the competition, so they went straight through to the Round of 16, where they were drawn against Mexico. That Spanish debut ended in a resounding 7-1 victory, a match in which Yermo scored three goals.

Italy awaited in the quarter-finals. In the trans-Mediterranean duel, the typical shortcomings of the Spanish team began to show: a lack of training, cohesion and killer instinct. After ninety minutes of normal time and half an hour's extra time, divided into two halves, the match ended in a one all draw. Three days later, a play-off match was played and Spain could do nothing to stop a rampant Italian side, who won 7-1.

The "narrative of failure" was present again in 1928 when it was suggested that what happened was due to Spanish “quixotism” in complying with the rules (only fielding amateurs) while the rest did not and fielded players who were “amateurs” only in name.

This sweet moment for Spanish football began at the end of 1924: the national team beat Hugo Meils' Austrians in Les Corts (Barcelona) in a match in which the national team continued to show signs of being a team of individuals (Zamora, Samitier and Gamborena) rather than one of cohesive team play. Spain’s win came thanks to goals from Antonio Juantegui (Real Sociedad) after three minutes and Samitier three minutes from time which gave Spain a 2-1 victory over the Central Europeans footballing powerhouses.

The year 1925 kicked off with a trip to Portugal where Spain won 2-0 with goals from Bilbao's Carmelo and Óscar from Santander. The same year also saw the national team's first European tour, with trips to Austria and Hungary which took them to play in Vienna and Budapest over a 10 day period.

Between 1927 and 1929 there was a period of transition in the national team until the arrival of José María Mateos on the bench as the stand alone national team manager. Manuel de Castro, Ezequiel Montero and Mateos himself had previously managed the Spanish team jointly in 1926-27 and had introduced numerous changes: 14 players made their debuts between 1926 (the 4-2 victory over Hungary) and 1927.

That year, on 29 May, a rare occurrence in the history of the national team took place, funnily enough the strange event would also happen again in 1949: the national team played two matches on the same day.

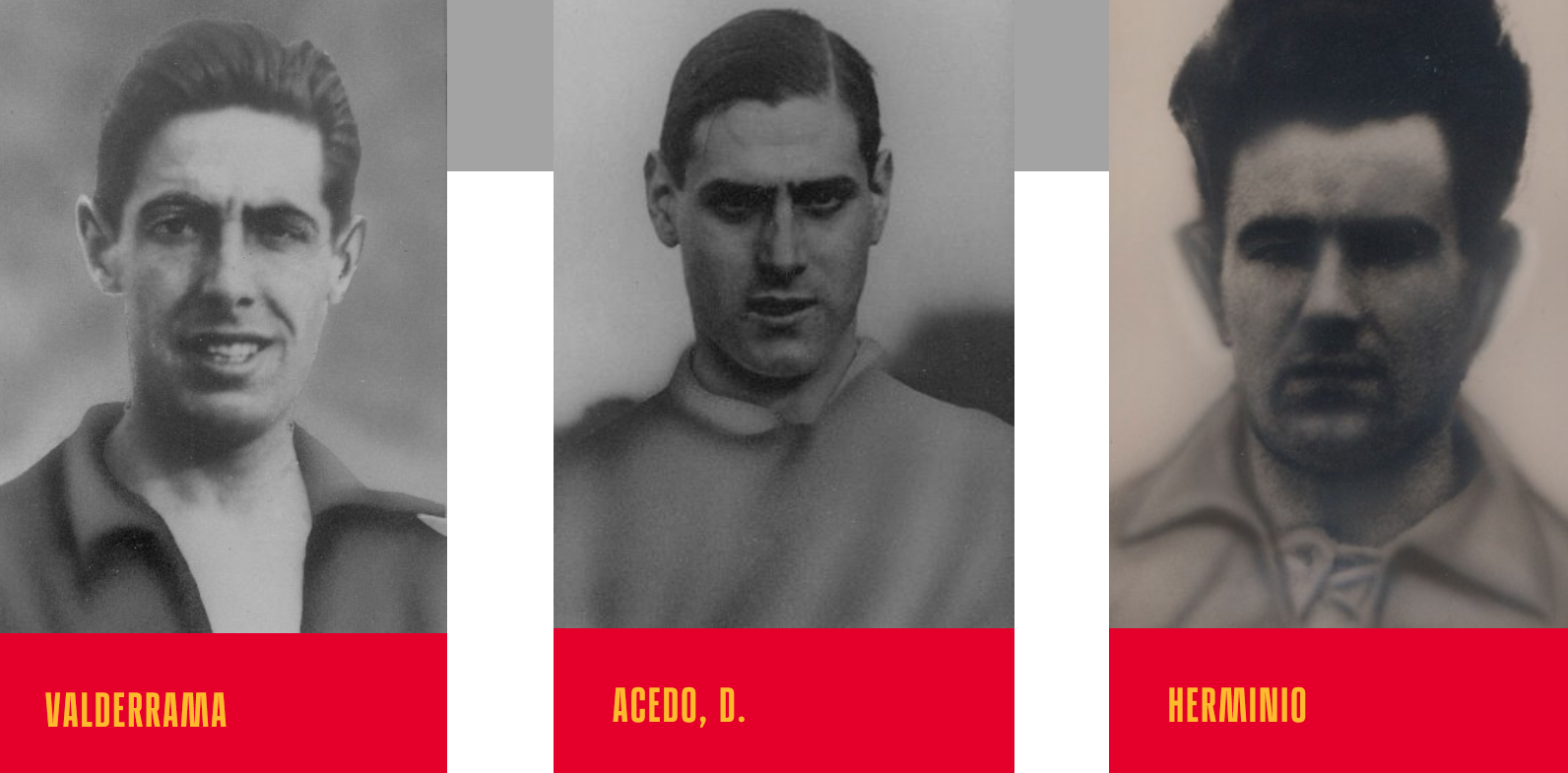

The national team played Portugal in Madrid, with King Alfonso XIII and the princes Don Juan and Don Jaime watching on from the Royal Box; and at the same time another Spanish team played Italy in Bologna - the RFEF only considers the match against the Italians to be official. In the Spanish capital Spain won 2-0 (with goals from Valderrama and Moraleda) and in Bologna they lost 2-0. The Estadio Metropolitano saw what one might call a "B team" play, with future coach Guillermo Eizaguirre making his debut.

1928 was a bitter year for the national team coached by José Ángel Berraondo (ex-Madrid player and ex-Real Sociedad coach), with only one win in five matches, failure to beat Portugal for the first time and early elimination from the Olympic Games in Amsterdam.

Before the Olympic Games, the team had two draws in two friendlies: a 2-2 draw against Portugal in Lisbon and a 1-1 draw against Italy at El Molinón. The poor performances in both matches prompted Berraondo to hand in his resignation, which was not accepted, and he finally took the team to the Olympic Games.

The arrival of José María Mateos on the national team’s bench would mark a new era of great expectations.