History of the Spanish National Team (Part 9): Great expectations

Between 1942 and 1945, only a few matches were played due to it being an era of war. In this case the Second World War made it difficult to play international sport. On the horizon, still distant and uncertain at that time, there was a World Cup in Brazil which the Spanish national team hoped would be the moment of reaffirmation it needed. As such, the road to that moment was paved with great expectations

After the defeat against Italy in 1942, a new impasse began in the history of the national team that lasted until January 1945. It was a period of almost three years without international matches due to the difficulties caused by the Second World War, which was causing bloodshed across Europe and making it almost impossible for teams from different countries to play against each other.

When the national team returned to the field of play, first under Jacinto Quincoces, then Luis Casas, followed by Pasarín, and finally Pablo Hernández Coronado, they suffered an identity crisis as a result of an accumulation of bad results. It was only with the arrival of Armando Muñoz Calero as president of the RFEF and Guillermo Eizaguirre as coach in 1947 that the national team found stability, a way of playing and a style of their own, while at the same time being able to progress in a definite direction which, in the end, led to them competing successfully at the World Cup in 1950.

Adapting to the "new tactics" emerging from England

The national team gradually abandoned its traditional style, in which individual talent was given more importance than collective unity, and began to adapt to modern tactics and the "big talking point of the day" which was the introduction of the new tactics born in England decades before but which were gaining ground across the continent at the time.

Just as "laissez faire, laissez passer" seemed to be in decline in favour of centralised planning (the Soviet five-year plans, the American "New Deal" or the Spanish development plans of the 1950s), in football, models based on improvisation and individual genius were giving way to the emphasis on collective play

In the 20s and 30s, the individual inspiration and quality of Zamora, Samitier or Lángara had been enough for Spain to prevail in matches; but from the 40s onwards, the idea began to take hold that a more elaborate, team-based style of play was needed. Jacinto Quincoces recognised something of this when he stated in 1945 that:

"We used to have world class players and now there is a lack of them. We have a good class of players and nothing more".

It was no longer possible to base everything on the individual quality of the players, the time had come when focusing on teamwork was the way forward.

The period from 1945-47 was a period of instability on the Spanish bench, with a handful of coaches who did not even complete a year in the job coming and going: Quincoces was coach of the national team for seven months, Pasarín for half a year and Hernández Coronado for another seven months. The former left to coach Real Madrid and the latter preferred to leave to coach Valencia. Then, an in-house coach in the shape of Hernández Coronado took over the responsibility for the team until finally stability came with Eizaguirre.

In mid-1946, Pasarín called up his first squad of 18 players for the matches between Spain, Portugal and Ireland. After drawing 2-2 in Portugal and winning 4-2 in La Coruña, the team was based in El Escorial, where the card game tute and, to a lesser extent, chess were the most common distractions, along with writing long letters like Eizaguirre and Gonzalvo II did.

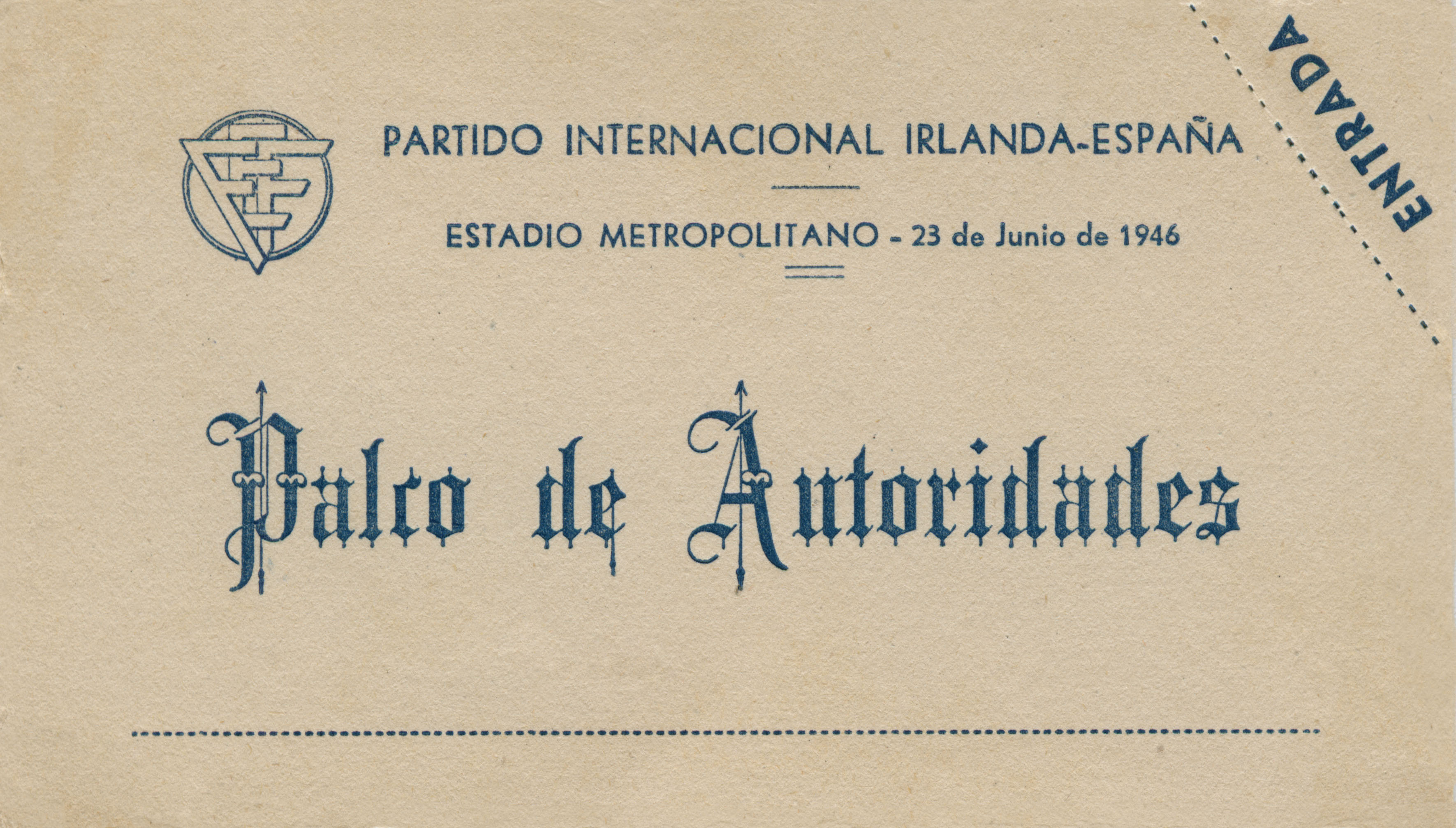

The match against Ireland took place in the midst of Spain's political isolation, so the event was used by the Franco regime as a way of showing that the country was not alone in the world. For this reason, the presence of the Head of State was particularly significant, as it was the first time he had attended a national team match. ABC noted that "on the arrival of the leader, accompanied by his wife, the crowd applauded him with overflowing enthusiasm". The player Ipiña went to the presidential box to offer the dictator's wife a bouquet of flowe

Spain, wearing white shirts and black shorts, took on an Ireland side who had just lost 3-1 to Portugal at the Metropolitano stadium. The national team went into the game with the idea that if they had beaten the Portuguese, it was logical that they should also beat Ireland.

However, Spain were beaten 1-0 by an Ireland side who, in the words of ABC journalist Gilera, "played the WM tactics beautifully". With a third defender (Vernon) neither Martín nor Zarra were able to pose any danger to opposition goal and the inside backs (Panizo and César) were eventually nullified by the midfielders. Pasarín brought on Zarra for Martín but the problem went deeper than a simple substitution, it was not a change of name but of the general tactics that was required.

The new systems such as the famous ‘WM’ tactic were proving superior over the Spanish style, which was still anchored in the tradition born in Antwerp in 1920 that continued throughout the following decades. In the match a most unusual occurrence took place: not even before half-time, Pasarín, in the face of the Spanish team's ineffectiveness up front and a stadium chanting "Zarra, Zarra" incessantly , decided to replace Mariano Martín with the Basque striker. The Barcelona centre-forward left the pitch with his head down crying, crying with rage.

The defeat, watched by some 60,000 spectators, opened Pandora's box in terms of establishing the idea that Spanish football was not on the right path, which made it urgent to undertake a process of modernisation. This idea would take root more and more strongly throughout the period 1946-48 and the feeling of decadence in the national team and, therefore, in Spanish football in general, would deepen, especially as the bad results were shown not to be isolated incidents.

The "myth of fury", cornered by the "myth of failure"

As so often before and since in the history of the national team, the "myth of fury" was cornered by the "myth of failure". Against Ireland, the team showed major problems: it lacked a team game, relying more on improvisation, speed, fury and clinical finishing than on tactics and an overall vision.

Added to this problem was the lack of continuity on the bench. After seven months Quincoces resigned in 1945, in July 1946 Pasarín left his post to take charge of Valencia. Their legacy would be arrival of the three men destined to mark the history of the national team (Barcelona´s Gonzalvo III and Bilbao’s Iriondo and Panizo) who made their international debuts on the bench.

In this context, in October 1946, a new coach took over: the Federation's Committee of Directors decided to appoint one of its own members, Pablo Hernández Coronado, to the post.

Hernández Coronado was national coach at three different times. The first in 1947 in two matches against Portugal and Ireland; the second in 1955 when Ramón Melcón resigned and a third in 1962 at the World Cup in Chile.

"Today we are going to play our style".

Within the growing debate, which was nearly ever-present in the media, between supporters and detractors of the WM tactical system, Hernández Coronado was not a man very open to modern tactics.

In fact, in the training session prior to the match against Ireland, when giving instructions, he addressed his players in the following terms: "Today we are going to play our style", which meant not placing the centre-half between the two defenders or moving the two inside backs back to form a box midfield with the two midfielders.

Intensely dedicated to watching matches in October and November, on 24 December he announced the squad of players shortlisted to play a preparatory match against San Lorenzo de Almagro, an Argentinian team on tour in Spain. The list included the return of the great Isidro Lángara, who that season had returned to play for Real Oviedo at the age of almost 34. If the defeat against Ireland was a first wake-up call about the identity crisis of the national team, the loss against San Lorenzo by 7 goals to 5, despite only being a friendly match, turned out to be a devastating blow. The classic Spanish fury (speed, improvisation and long passes) succumbed to a more composed, short-tempo, tactically driven Argentina side.

A second and more serious wake-up call, which set alarm bells ringing, came at the end of the same month of January. Spain were defeated for the first time by Portugal and by the embarrassing scoreline of 4-1.

The Spanish defeat, the first in 25 years of Spanish-Portuguese duels and with 7 players from the then Atlético de Bilbao, came as a massive knock to Spanish confidence, showing that "Spanish enthusiasm had little to do against the "cohesion of the whole". "Our football is undoubtedly going through a crisis", were the words of Hernández Coronado, who knew where to point the finger.

Hernández Coronado's brief and lacklustre tenure left a legacy of a national team mired in poor results and a lack of confidence in their game and their potential. The coach himself described his time in charge of the team as "disastrous. Mainly, because in my first period as coach, we lost to Portugal for the first time in our history in 1947.

It was the turn of a coaching duo that would make history, the Guillermo Eizaguirre-Benito Díaz pairing (1947-1950).