History of the Spanish National Team (Part 13) The failure of 1958 and Euro 1960

The Spanish national team ended the 1950s in failure, competing in their first European Championships while preparing, inadvertently, for what would be the basis of its first continental title: the 1964 European Championships. All this, with political intrigues in between, such as a match in 1960 against the USSR that was never played.

In the 1960s, Spain returned to the elite of world football, leaving behind the hard times of the previous decade: during this time they would play in two World Cups (1962 and 1966) and won a European Championships in 1964.

The period from the failure of 1958 to the conquest of the European Championships in 1964, with the epilogue of the '66 World Cup, can be divided into two clearly marked stages: before and after the appointment of José Villalonga as head coach.

First was the period of frustrated expectations (1958-62): as in the previous stage (between 1951 and 1957), the position and role of the coach was one that was constantly in a state of flux. This dynamic would end when Villalonga took charge of the team from 1962 to 1966 as head coach, from 1960 he had been a constant presence in the coaching team. The period before Villalonga was marked by a lack of continuity: in four years there was one coach/trainer -Meana-; two Technical Committees with their respective coaches -Helenio Herrera, José Villalonga and Luis Miró- and two single head coaches -Pedro Escartín and Pablo Hernández Coronado- accompanied by two coaches -Miguel Muñoz and Helenio Herrera (HH).

Meana, who had taken the reins of the team in 1957, continued as head coach throughout 1958 and half of 1959 despite failing to qualify for the World Cup. However, just a few days before the national team played its first match of the Euro qualifiers, Meana resigned (or jumped before he was pushed). At that time, the Royal Spanish Football Federation, chaired by Dr. Alfonso Lafuente Chaos, strengthened the role of the Technical Commission - which had existed since 1955 - composed of a coaching duo to replace Manolo Meana. Until 1957, this Commission was made up of three doctors and former footballers. The trio was formed by doctors Ramón Gabilondo, Jaime Lazcano and José Luis Costa. After Lazcano's departure, Gabilondo and Costa were responsible for appointing Helenio Herrera as national team coach. In August 1959, the journalist from the Barcelona daily Mundo Deportivo, José Luis Lasplazas, took over the post vacated by Lazcano in March 1957.

Until 1960, this trio was dedicated to appointing the men who would be on the national team bench as head coach. As they did with HH, who was at that time, 1959, in charge of Barcelona; this structure continued with José Villalonga of Atlético de Madrid and Luis Miró of Sevilla. Under HH, the team began to take shape, advanced to the quarter-finals of the European Championships, comfortably eliminating Poland, and achieved resounding victories over Italy and England, although they were unable to go beyond the quarter-finals when the USSR crossed their paths and the Franco regime prevented the team from playing the Soviets in the knock-out matches.

From 1960 until qualification for the World Cup in 1962, it was time for a single figure to take on the job of head coach and Pedro Escartín was accompanied by assistant coach Miguel Muñoz. The national team went into the World Cup in Chile with the same structure but with different names: Pablo Hernández Coronado as selector and Helenio Herrera as head coach.

After the World Cup fiasco, José Villalonga took over the reins, not only in a coaching role as in 1960, but also as a selector. He would not relinquish the reins until 1966, during which time he won the first title in the history of the Spanish national team, the 1964 European Championships.

Meana, with a view to the two big events in the offing, the first European Championships scheduled for 1960 and the 1962 World Cup in Chile, was working to build a team that would enjoy continuity and forge a personality of its own. One of the keys to this was the attacking line of Miguel, Kubala, Di Stefano, Suárez and Gento. However, in June, the surprise came: Meana resigned after a meeting with the president of the RFEF, Lafuente Chaos, in which discrepancies appeared between the two.

The end of Meana's era came after a meeting of the Executive Committee of the Royal Spanish Football Federation focused on examining the situation in the national team and its possibilities with a view to the European Championships and World Cup 1962. The Committee concluded that to avoid the failures of '54 and '57 there was an "unavoidable need for methodical preparation, without which any national team loses effectiveness". The agreements reached concerned the division of roles between a Technical Committee in charge of selection and a national team coach.

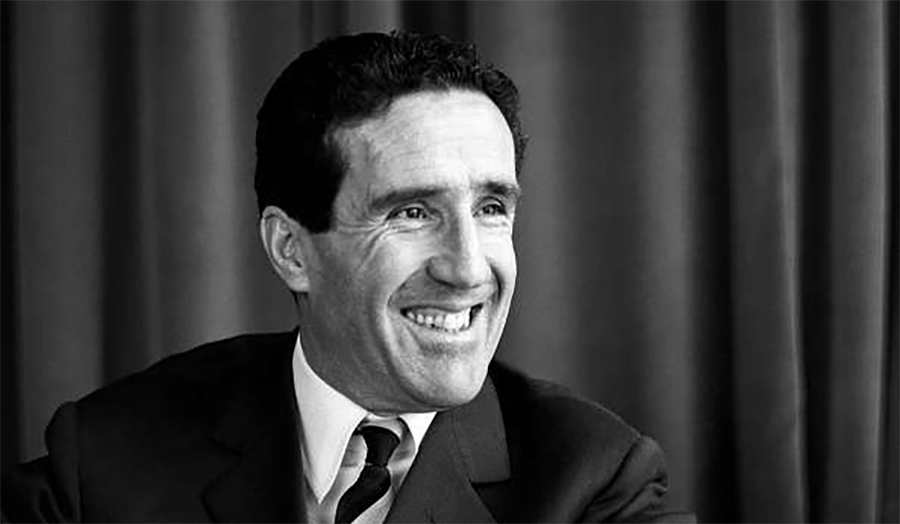

The RFEF's new man was Helenio Herrera, better known as HH. His aim was to adapt the national team to the times, renewing and modernising it with the aim of returning to the elite. Herrera, at that time coach of Barcelona, a team with which he won two La Liga titles and the 1959 Cup, became the man called upon to replace Meana not as manager but as head coach of the national team. HH was an experienced and cosmopolitan man, self-made, cultured and fluent in several languages; an innovator concerned with tactical preparation, the use of the magnetic board and the promotion of the figure of the "sweeper" and man-to-man marking. He came to the national team with a wealth of experience. Now, in 1959 he had another challenge ahead of him: for Spain to do well in the new competition created by UEFA.

In June 1959, the national team began its journey in that first European Championships. The Technical Committee (José Luis Costa and Ramón Gabilondo), in their initial squad, relied heavily on Barcelona players, with 8 called-up. and Madrid (4) with additions from Atlético de Madrid and Bilbao, both with two players each and one each from Valencia and Betis. Of note was the return of Ramallets, absent since 1957, and the presence of an emerging talent, the Betis player Luis Del Sol.

The team was based in La Berzosa (Madrid) under the orders of Helenio Herrera to prepare for Spain's first match at a European Championships: the opponent was to be Poland. A few days earlier, HH had outlined the pillars of his project. Starting with his effort to demonstrate that neither his status as a foreigner (born in Buenos Aires in 1910) nor as, at the time, the fact he was coach of Barcelona were obstacles to his role at the helm of the national team "for eleven years I have felt united to the great family of Spanish football... Spanish blood runs through my veins... when Spanish football was recently in the World Cup it did so with Benito Díaz, who was also coach of Real Sociedad at the time"

His great aspiration was to create what he called "Club Spain" to give the national team an air of greater cohesion. HH, who began to take Ángel Mur with him as a masseur, sought to implant this team dynamic in the national team with more regular and regular twice weekly training sessions. Before leaving for Poland, the team maintained a training regime of morning sessions at the Metropolitano.

HH was very meticulous about meals, where, for example, he dispensed with spices and fats, as well as rest: he had the players get up at 9 a.m. and go to bed at half past ten. The rest that HH tried to ensure for his players was twelve and a half hours each day, and the schedule included attending mass. In fact, before the match against the Poles, the players attended a religious ceremony.

His great aspiration was to create what he called "Club Spain" to give the team an air of greater cohesion.

HH saw the match against the Poles as a necessary turning point for the Spanish national team. In that sense, he tried to send a clear and forceful message: "We want the result in the Chorzow stadium in Katowice to be the bombshell that announces the resurgence of Spanish football". And so it was when in Katowice, at half past five Polish time, Spain played their opening match at a European Championships.

HH opted for Ramallets as goalkeeper, Garay in defence alongside Olivella and Gracia; Segarra and Gensana were the masters of midfield, supported by a more advanced player in Luis Suárez; and in attack Di Stefano and Mateos as the striking duo accompanied on the wings by Tejada and Gento. That would be the basic team throughout HH's tenure, which triumphed in his first European Championships match.

They displayed great goal scoring, winning 2-4, and their midfield had a great game. After Poland went ahead through Pohl, Di Stefano scored twice, both in combination with Madrid's Mateos, and then Luis Suárez brought the score to 1-4, which the Poles made 2-4 in the 72nd minute.

Suárez, scorer of Spain's first goal at a European Championships, would recall years later that

"When we travelled to Poland we were not aware of the stature and importance that the tournament subsequently acquired. You start to realise the magnitude of the event when you see the level of play and when the media also play their part in making it bigger.”

The national team came out of the match feeling very much stronger, as Mundo Deportivo highlighted, headlining its report with a significant "FINALLY!

El Escorial, the traditional Felipe II hotel, hosted the squad before the second leg against Poland, which was held in Chamartín at 8.30am. HH chose the same players who had taken the field in Katowice (except for the introduction of Kubala for Mateos) and the result was another easy and convincing 3-0 victory. Goals from Di Stefano in the first half and from Gensana and Gento in the second, with Kubala playing a decisive role, tipped the scales in favour of a Spanish team that, despite the result, came in for harsh criticism from a public that were expecting much more.

Not only did Spain's 4-2-4 win out against the Polish block, but HH seemed to have found a settled eleven. The national team, knowing they were superior, and with the tie looking wrapped up, did not play well and despite the victory and qualification, the Spanish players left the pitch upset and crestfallen, as can be seen in the photo:

All that remained was to learn the opponent for the next phase, which came out of the draw held in Paris: Spain were paired with the USSR and the presidents of the two federations (Lafuente Chaos and Valentin Granatkin) fixed the dates for the fixtures: the first leg on 29 May in Moscow, and the second leg on 9 June in Madrid, with a possible play-off in Rome or Paris.

In January 1960, there was nothing to suggest that there would be no match against the Soviet Union. A source close to the RFEF spoke:

"If Spain, as we all hope and expect, eliminates Russia and goes through to the semi-finals, they will have to play the finals in the designated country, which we also hope will be ours. Naturally, this will result in a readjustment of the Cup schedule".

On 13 January, the USSR announced its 28-man provisional squad for the match against Spain, and in February the Spanish resumed their preparations. In March 1960, all efforts continued to focus on preparing for the knock-out match against the USSR. As such, friendly matches were set up with two of the world's top teams, England and Italy.

In May, HH, recently sacked as Barcelona coach, led the a squad training camp, at the Felipe II Hotel in El Escorial and with training sessions at the Metropolitano and Chamartín, with a view to the imminent preparatory match against England and the Euro quarter-final against the USSR. Two teams were formed, one for the match against England and the other - the B team - to play Morocco.

On Friday 20 May, Helenio Herrera drew up a list of 20 players for the match against the Soviets. The called-up players were scheduled to meet in Madrid on Tuesday 24 May to travel to Moscow on 27 May. After this announcement, rumours began to spread. Luis Suárez recalls that "something was going on, we were hearing things, but we didn't think that we weren't going to play". The players arrived at the training hotel and at twelve noon they were given the news. On Wednesday 25 May, the same brief and succinct statement appeared in all the Spanish press:

"The Spanish Football Federation has informed the F.I.F.A. that the football matches between the national teams of Spain and the USSR for the European Nations Cup are suspended".

The decision not to play against the USSR was finally taken at the last Council of Ministers, held in Pedralbes, where the theories of Carrero Blanco and Alonso Vega (Ministers of the Presidency and the Interior, respectively) were victorious. Proof of this is that Alfredo di Stéfano received an explanation from the President of the Federation, Alfonso Lafuente-Chaos, who told him that it was an order taken "by those in charge. We are not going to Moscow, Franco said so". Something similar reached Luis Suárez:

"We were sure that we could beat them and be European champions, but they told us that there were orders from above, from Franco, and that there was nothing we could do".

Lafuente Chaos, the president of the Federation, hurriedly travelled to Paris to look for a solution: to play on a neutral ground, to play the two matches in Moscow, renouncing the economic rights, but the Russians rejected any other option. The USSR took the matter to UEFA, which decreed Spain's expulsion from the European Championships and the automatic passage of the Soviets to the finals. Ramón Ramos in "The Russians are coming! Spain renounces to the 1960 European Championships due to Franco's decision", he argues:

"The Government decided that Spain was not going to play the matches but the Federation tried by all means to revoke that order and convince Franco to allow the national team to play in Moscow and that the following week the Soviet team would come to Spain".

According to Ramón Ramos, the regime's great concern was not so much that Spain would go to Moscow, but that "a Soviet delegation would travel to Madrid and altercations would occur". There was also the symbolic fact that a red flag of the USSR with the hammer and sickle would be flying in front of Franco at the Bernabéu:

"Everyone knows that Spain refused to play, but the novelty is that Spain went to their first European Championships despite the fact that already in 58 it had consulted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the latter had replied that it was the Government's criterion that no Spanish team should enter competitions in which there might be the possibility of facing Russia. In the foreign press, the Spanish withdrawal was justified in the context of this incident and the failure of the Paris Conference".

Ramos maintains that in the Council of Ministers in which it was decided that Spain should not play against the USSR, there was a debate between the hardliners in the regime, above all the military, and the more open-minded, who tried to show that sporting success helped to improve the external image of any political regime, "whether it was a right-wing dictatorship, communist, democracy, republic...". In the end, "the most conservative within a very conservative regime" imposed their theories.