History of the Spanish National Team (Part 12): The disappointing 50s

The Spanish National Team passed the test that was the 1950 World Cup with flying colours, but its journey through the following decade was far from positive. Within this period, 3 distinct phases can be distinguished, which shows the tangible instability that surrounded the team in those years.

The period between 1950 and 1964, from the fourth place finish at the World Cup in Brazil to the conquest of the 1964 European Championships, can be divided into three main parts for the Spanish national team.

The first two (1950-54 and 1954-58) were marked by the national team's failure to reach two consecutive World Cup finals.

The third (1958-64) was far more positive as it included participation in the 1962 World Cup and two European Championships in 1960 and 1964 and culminated with the great success, Spain won the European Championships held in Spain in 1964.

Spain’s presence among the elite would continue, though without such positive results, at the 1966 World Cup and the 1968 European Championships.

| Selector | Coach | Years |

|---|---|---|

| Yceta-Alcántara-Quesada | Benito Díaz | Dec ‘50 - Oct ´51 |

| Ricardo Zamora | Nov 51 - Oct 52 | |

| Pedro Escartín |

Luis Casas, Pasarín, Coach; José Villalonga, Physical trainer |

Nov 52 - Sept 53 |

| Luis Iribarren | Ramón Encinas | Oct 53 - Mar 54 |

| Ramón Melcón |

Benito Díaz José Villalonga |

Sept 54 - May 55 Apr 55 - June 55 |

|

José Luis del Valle, Pablo Hernández Coronado, Juan Touzón y E. Jiménez Millás |

Luis Miró | June 55 |

| Guillermo Eizaguirre |

Luis Miró (Sept 55 - May 56) Jacinto Quincoces (May 56) |

Sept 55 - Sept 56 |

| Manuel Meana | Sept 56 - 1958 |

Iribarren, who was assisted by the experienced Ramón Encinas, “Moncho Encinas”, only had two months to prepare after the unexpected resignation of Pedro Escartín in September 1953. The former international referee had been in charge of the team for almost a year and a half and it would have been logical for his work to culminate in leading the team into the World Cup qualifiers. However, worn down by heavy criticism stemming from poor results and unconvincing play, Escartín resigned just four months before the decisive match against Turkey, the team against which Spain was playing for a place in the World Cup finals.

The first of the two matches against Turkey was held on January 6 1954 in Chamartín, and with Franco in the box, Spain won 4-1.

The most notable new face for the second leg was the presence of Ladislao Kubala, who had obtained Spanish nationality on June 1, 1951 and was called up even though he had not been in Spain for the three years required by FIFA to be eligible to play.

And in Turkey the first chapter of the “disaster” was consummated. A poor performance by Alsúa and a bad game by Kubala were the prologue to the error leading to the winning Turkish goal. The Spaniards, under enormous pressure going into the match, saw the match's decisive moment after 15 minutes: Pasieguito failed to cut out a ball close to the area and the Turks did not waste the opportunity to score what was a demoralising goal for our national team.

With both teams with a win each, a play-off match was held three days later in Rome. When the match was about to start, something unexpected cropped up that unsettled the Spanish team and altered all their tactical plans: Colonel Zamalloa (head of the delegation) hurried into the dressing room, asserting that Kubala could not play in the match because a telegram had been received from FIFA forbidding him from doing so. Laszi's place was taken by Pasieguito.

Zamalloa had been given a telegram by Otorino Barassi, president of the Italian Football Federation and FIFA commissioner, which said in French: ‘Attention Spanish team regarding the situation of the player Kubala’. It did not explicitly prohibit his participation, but it caused such fear of disqualification that the player ended up not taking the field. Zamalloa and the president of the RFEF declared days later that it came from a specific World Cup Central Committee.

For the Spanish players, the whole thing was like an earthquake, as Escudero acknowledged:

‘The players were not shown the infamous telegram, we didn't see it, but we were told that it arrived not forbidding Kubala from playing but hinting so. The fact is that Laszi and I found out together that something was going on because while we were all kitted up, in the tunnel, the masseur Rafa arrived and told Kubala to go back because there was a problem with his registration. He came back and minutes later we went out onto the pitch and Pasieguito joined us in his place. At half-time we were all asking ourselves the same question: how the hell are they stopping him from playing here when he played three days ago in Istanbul? And if there was an infringement there, why haven't they already sanctioned Spain?’

Spain were not able to cope with all this tactical upheaval and: at the Olympic Stadium in Rome, the national team was held to a 2-2 draw, with goals from Arteche and Escudero.

At the time, penalty shoot-outs were not yet established as a way to decide the winner, so a draw was done to see which team would get a place at the World Cup. A child, the famous ‘bambino’ Franco Gemma, was blindfolded and pulled a piece of paper out of a cup with Turkey's name on it. Spain was out of the 1954 World Cup.

It was a serious blow for Spanish football. The elimination and the controversy over the telegram triggered a deep crisis in Spanish football. Sancho Dávila and the board of the Federation resigned, as did Armando Muñoz Calero, who, in turn, resigned from his post at FIFA, citing the injustice Spain received. He accused FIFA of not wanting to make an enemy of Hungary and that was why it had not resolved the ‘Kubala case’. Iribarren, for his part, stepped down as coach.

This, however, would not be the only debacle for the national team in that decade. A 1955 defeat against France sank Melcón and a 1956 loss to Portugal sank Eizaguirre. These setbacks were the prelude to the second great failure of the decade: the 1957 defeat in the qualifying round for the World Cup in Sweden. The national team, then under the tutelage of Manuel Meana, prepared for the World Cup qualifiers with resounding 5-1 victories over the Netherlands and a 3-1 win over Stuttgart at the Metropolitano.

But when the official qualifying matches arrived, the horizon soon darkened. In order to reach the World Cup finals, Spain had to face Scotland and Switzerland in their group. Their qualifying campaign was not all bad, losing only one game, drawing one and winning two, scoring eight goals and conceding seven. The problem was not that the inevitable happened (losing to Scotland in the British Isles) but that the unexpected happened: drawing with Switzerland in Madrid. The unexpected bad result occured in the Chamartín stadium, where Franco came to watch the match. That first group match brought a nasty surprise: a draw against the Swiss in a rain-affected match.

Indeed, the expected victory over the Swiss, frustratingly, did not happen. Spain started as favourites thanks to the great forward they had at their disposal: Miguel (a right winger from the Canary Islands with exquisite technique and intelligence), Kubala, Di Stéfano, Luis Suárez and Gento. The draw became the main reason, though not the only one, for Spain's absence from Sweden 58 as Meana's team were unable to turn things around after that setback.

Hampden Park was the scene of a very painful defeat (4-2) for a Spain side who, after this setback, would find it almost impossible to qualify for the World Cup. Scotland's speed and quality midfield play nullified the national team. For the return leg, Spain, with only few fans turning up in Chamartín, avenged the defeat at Hampden Park by thrashing the Scots 4-1 with goals from Mateos, Kubala and two from Basora.

With this victory, Spain, in second place with three points, were one point behind Scotland who had four points and qualification in their own hands: all they needed was a win over Switzerland. The Spanish team, by beating the Swiss, could reach 5 points, but a Scottish victory would put the British team on an unattainable 6 points. And November 1957 saw the second great disappointment of the decade.

Scotland's 3-2 win over Switzerland meant that Spain were out of the World Cup even before they met the Swiss. Therefore, after the Scottish victory over the Swiss, a match of no consequence was played, as it was impossible for Spain to finish first and reach the World Cup finals. Two goals from Kubala and two more from Di Stefano, plus two assists from Suárez and one from La Saeta confirmed Spain's superiority (1-4) against the Swiss.

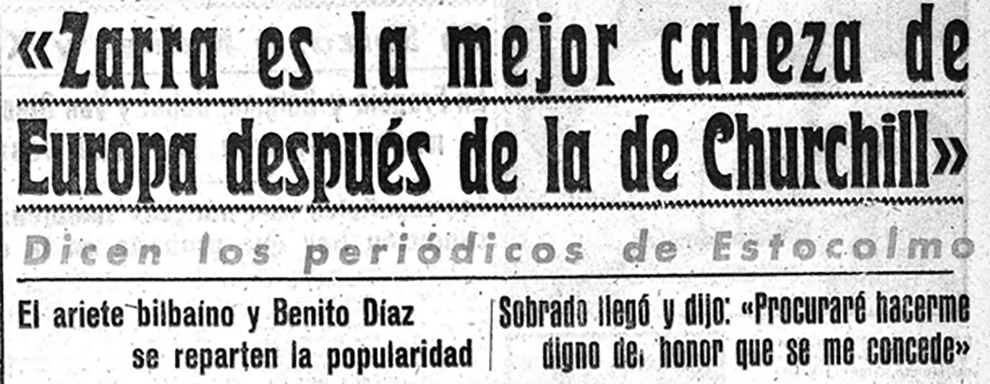

The farewell that marked the end of an era was that of Telmo Zarra in 1952 when injury kept him out of the national team and then relegated him to the bench. Zarra played his last match for the national team in 1951 (the goalless draw against Sweden in June) but was still eligible for selection, even travelling to Argentina and Chile in 1953 as a substitute for Kubala. He even played alongside Kubala, the player who would displace him from the starting line-up, when, in preparation for the World Cup in Brazil, the national team played against Hungary.

‘In that warm up match I saw Kubala for the first time. He made a great impression on me. He stood out from the rest as a truly extraordinary player. He was a great inside player at the time, although he switched to the centre-forward position seamlessly. I think that's when I saw Kubala at his best. Even better than he is today,’ the Basque player later confessed.

After the injury he suffered at the end of 1951, Zarra was no longer a starter and Escartín even sent him a letter explaining the reasons and inviting him not to lose heart. ‘When Escartín told me that he would not play, I felt terribly down’.