History of the Spanish National Team (Part 5): World Cup 1934

Our story of the Spanish National Team continues in the 1930s, before the Civil War abruptly interrupted the history of the country and the national team itself. We continue the story with a great milestone: Spain’s first appearance at the World Cup. An appearance that, despite ending in bitter defeat, fostered the connection between the team with their fans and laid the foundation that even a civil war conflict could not completely destroy.

To reach the World Cup for the first time, they had to overcome a two-legged qualifier against Portugal in 1934. In Madrid, Spain triumphed 9-0 against the Portuguese in a match attended by the President of the Republic, Niceto Alcalá-Zamora. In the away match in our neighbouring country, the team led by García Salazar secured a 1-2 victory with a narrower margin.

The exhibition of attacking quality at Chamartín (Madrid) was formidable: Spain played exceptionally well, not only due to Lángara's killer instinct in front of goal (5 goals) or Luis Reguerio's brace, but also thanks to the defensive solidity of the Quincoces-Zabalo partnership at the back. Not to mention the playmaking efforts of Marculeta and Cilaurren who linked up well with Regueiro and Chacho, and quick breaks from Gorostiza and Ventolrá, who scored one goal.

The return match in Lisbon was not so straightforward, although preparations for the match had gone well with intense training sessions in Aranjuez (near Madrid). Eventually, the national team emerged victorious (1-2) with two goals from Lángara. The Spanish did enough to prevent the need for a play-off match, which was initially planned to take place in Vigo.

Once their ticket to the tournament was secured, the team prepared for the event by playing three friendly matches against Sunderland who played in the top division of English football. The first ended in a 3-3 draw (two goals by Chacho) and took place at San Mamés. The second was held in Madrid (a 2-2 draw), and the third in Valencia, where Spain lost 3-1.

Spain Manager Amadeo García Salazar took two goalkeepers to Italy: Ricardo Zamora (Madrid CF), who had been a safe pair of hands in the Spanish goal almost continuously since 1920, and Juan José Nogués (Barcelona). Guillermo Eizaguirre, who had a broken arm, accompanied the team in a support role.

García Salazar, with Sevilla's coach Ramón Encinas as his right-hand man, relied on two defenders from Madrid (Ciriaco and Quincoces), along with Zabalo (Barcelona) as the defensive spine of the team. In the midfield, the men who travelled with the team were Cilaurren and Muguerza (Athletic Club); Solé (Español); Marculeta (Donostia) and Fede (Sevilla).

Although the manager wanted to have the veteran Gamborena, he couldn't make the squad due to sickness. The forwards in the squad were wingers Lafuente, Gorostiza, and Irarágorri from Athletic Club, Ventolrá from Barcelona. As for inside forwards, there were Luis Regueiro (Madrid); Chacho (Deportivo); Bosch (Español), and Lecue (Betis); Finally, Lángara (Oviedo) and Campanal (Sevilla) were the central strikers.

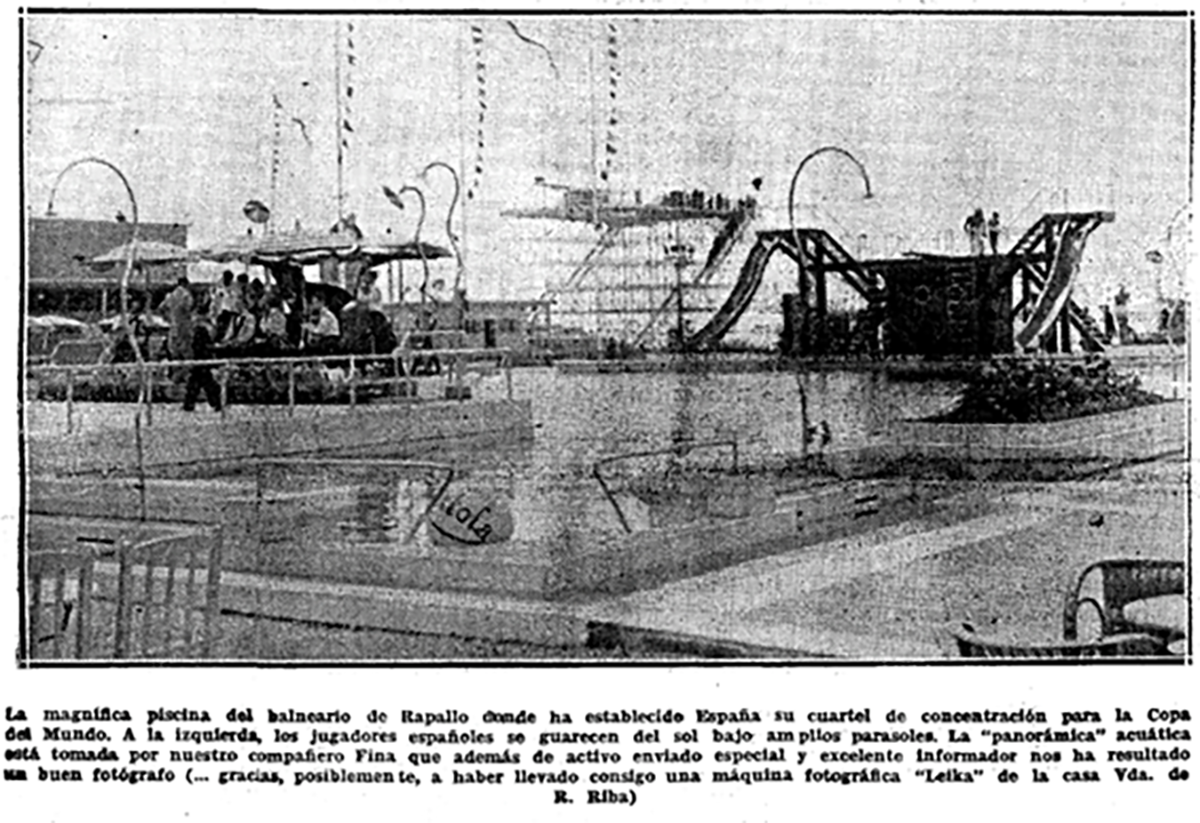

The team’s basecamp was the Rapallo spa

After building up for the tournament staying in Valencia and later in the Tibidabo area of Barcelona, the squad were looking forward to going to Italy. The travelling party left on May 24 from Barcelona to Genoa on the ship "Conte Blancamano," on which the Brazilian team, their first opponents at the World Cup, were also passengers. In Italy, the Spain team stayed at the Rapallo spa, a splendid setting captured in a photo below by the special envoy sent by the Mundo Deportivo newspaper to follow the squad at the World Cup.

The team prepared for their World Cup debut in Rapallo, on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, with extra focus on keeping the players in excellent physical condition. On the day before the match against the Brazilians, the starting lineup was confirmed. García Salazar opted for the defensive trio from Madrid composed of Zamora, Ciriaco, and Quincoces. The midfield was made up of Cilaurren, Muguerza, and Marculeta.

The great Athletic Club team of the 1930s not only dominated the makeup of the midfield with Muguerza and Cilaurren but also the forward line with Ramón de la Fuente. La Fuente played on the right wing and José Iraragorri as the right inside forward, with Gorostiza on the left wing. The Oviedo born Lángara played as centre forward and the Betis player Lecue, playing as left inside forward, completed the attack.

The first World Cup

Spain played three matches at the 1934 World Cup in Italy. The first one was in the Last 16 against Brazil, a team featuring stars such as Leonidas, Waldemar, and Luisinho. The match was played on May 27, 1934, with the old Marassi stadium (now called Luigi Ferrari) in Genoa as the stage for the clash.

Brazil came in as the favourites and top seeds against a Spain side that was not expected to go far in the competition. Spain felt aggrieved at not being a top seed, which is perhaps why, as a form of compensation, the Federation President, Leopoldo García Durán, was chosen as a member of the FIFA Executive Committee.

The Spain team managed to put the match to bed in the first half an hour: Iraragorri scored in the 17th minute, converting a penalty, and Lángara added two more goals in the 25th and 28th minutes. The Brazilians' response could only muster a consolation goal, scored by Waldemar de Brito in the 55th minute. With the victory, Spain advanced to the quarterfinals, where they would face the World Cup hosts, Italy, who had defeated the United States 7-1 in the round of 16.

In the quarterfinals against Italy Spain took on a team that were not only the hosts but also backed by the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini, who had staked Italian honour on his country’s success at their home World Cup. At the Rapallo Spa team basecamp, the days leading up to the match against the Italians all eyes were focused on the injured Marculeta and the uncertainty of whether Lecue, who had put in a subdued performance against the Brazilians, would play. The team travelled to Florence by train, where they were received, in a gesture of great sportsmanship, by the Italian coach, Vittorio Pozzo.

The Battle of Florence

Both teams went head to head for a place in the semi-finals on May 31, 1934, at the Comunale stadium in Florence. Not only was it a highly competitive match but also one that was rough and even violent at times. The match has gone down in history as "the Battle of Florence." A clever training ground set piece routine between Lángara and Regueiro put the Spaniards ahead in the 30th minute . At the end of the first half the Italians equalised from a corner kick. The Spanish players claimed that the equaliser came after a clear foul on Zamora, who was being held by Schiavio. El Divino later explained in the ABC newspaper the injustice that the team had suffered, starting with an emotive "they stole the game."

In the second half, the referee also disallowed a Spanish goal scored by Lángara for a controversial offside, and the score remained at 1-1 even after 30 minutes of extra time, so a playoff match had to be played. For Quincoces, as for Zamora, the "Battle of Florence" was a "robbery".

"They robbed us in both matches because we were better than the Italians, of course, and if it weren't for partisan refereeing decisions, we would have knocked Italy out. In the first match, they scored the goal after a clear foul, the Italian attackers roughed Zamora and the other defenders up, and in the end, Ferrari Giovanni scored with his head. I imagine that the referee, the Belgian Baert, stood there thinking of giving the foul, but the crowd shouted incessantly, and in the end, he gave in to the pressure and awarded the goal... And the injustice did not stop there because in the second half, Moncho de Lafuente showed some great solo skill, escaping from the Italian defenders, risking his legs while doing so, and in an individual play, scored to make it 2-1. And here came our surprise because the referee seemed to have disallowed it just because he wanted to. There is no other explanation because when he told us it was offside, we burst into laughter because La Fuente had dribbled all by himself, without having received the ball from his teammates."

The play-off against Italy was played the next day in Florence, with seven Spanish players absent (Zamora, Lángara, Ciriaco, Gorostiza, Fede, Iraragorri, and Lafuente) after picking up knocks in the first match. The team lost by the narrowest of margins in a match marked by Bosch's injury, which left the Spanish team even more weakened, especially on the left flank.

Everything seemed fixed for Italy to advance because, as ABC and Mundo Deportivo argued, Spain "should" be eliminated, and "finally," the path had been cleared for the host country to progress.

A cartoon from Mundo Deportivo vividly illustrates how the balance was tipped in favour of the Italians.

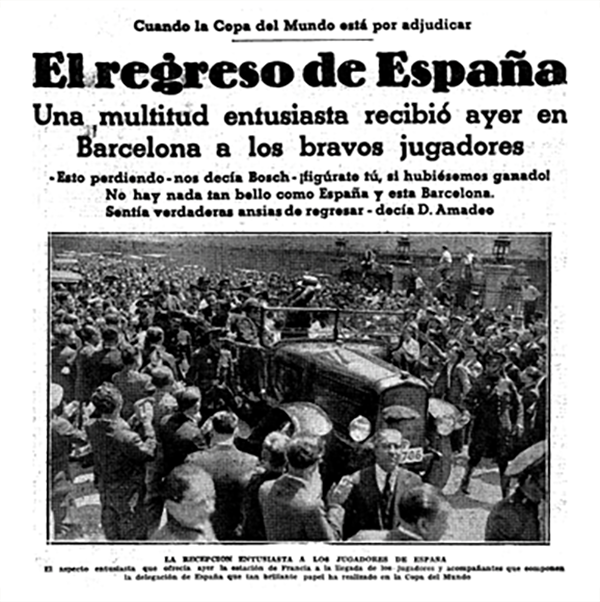

Those players who were in Italy, like those in Antwerp 14 years earlier, were greeted as heroes when they made their way back to Spain and on their arrival in Barcelona on 5 June. Welcomed with the knowledge that in spite of the painful elimination, they had given a great image of themselves and everyone had the feeling of having been victims of injustice.

Spain left a great impression at the 1934 World Cup in Italy for three main reasons:

a-. The quality of their players

It was one of the most competitive and highest quality squads Spain had ever sent to an international tournament. In fact, the official World Cup magazine chose Zamora as the best goalkeeper and Quincoces as the best left back at the World Cup. Muguerza, the axis of the midfield who drove the team's attacking play and organised the defensive unit, was chosen as the fourth best centre half and Marculeta as the second best left midfielder, Lángara was selected as the second best centre forward and Regueiro as the third best left midfielder.

b-. For the recovery of their international prestige

Spain, silver medallists at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics, had only suffered disappointments since then, with resounding failures at the subsequent Olympics: in 1924 and 1928. The friendly victories over England, Italy and France had compensated somewhat, but they were not enough. That was why the magnificent performance at the 1934 World Cup, eliminating Brazil in the Round of 16 and pushing hosts Italy all the way, sparked a new period of euphoria around the Spanish team. In this sense, the ABC newspaper, after the national team had been eliminated from the World Cup, claimed that the Spanish team had "regained its prestige" because "at this moment they are shining brightly" because "at this moment Spanish sport is shining brightly in the eyes of the world once again".

c-. The validation of their ‘fury’ playing style

The "fury", a distinctive element of the national team's way of understanding football, throughout the 1920s and 30s gradually lost the prestige it had earned at the 1920 Antwerp Olympic Games. In particular because doubts arose about the validity of this way of playing as success on the pitch failed to materialise. However, the Italian World Cup once again revindicated "fury" as the essence of the game on which Spanish football should be based.

This, at least, is how Juan Deportista, one of the authors of the concept, argued in the newspaper ABC:

"The Spanish national team plays with the solid platform that their training gives them, that consistent shield that depends on tight organisation, appeared in Genoa first and again in Florence, and was able to find solutions to everything through what one can call "Spanish fury".